Recommended Reading | the Twenty Years of a Child Adoption Announcement Collector

The 1992 Adoption Law changed the fate of over 160,000 orphans in China. They were taken and adopted by foreign families, with about half of them going to the United States.

Disclaimer: For ease of reading, our site’s editors have made appropriate modifications to the content without violating the original meaning. We hereby declare that this article only represents the author’s personal views, and this site serves merely as an information display platform, aiming to help readers gain a fuller understanding of historical truths.

The 1992 Adoption Law changed the fate of over 160,000 orphans in China. They were taken and adopted by foreign families, with about half of them going to the United States.

Today, new policies have announced the end of international adoption.

Two years ago, Shoulouchu documented the story of Lannie, a Chinese-American woman. For twenty years, she has been collecting information on abandoned children from Chinese newspaper announcements, compiling the children’s information into a vast database and providing it free to those seeking their families.

Her work has helped many families and has become a testament to twenty years of international adoption. My article records just a small part of this great endeavor.

International adoption has ended, but the cross-racial compassion will continue to shine. Two numbers deserve to be highlighted again and again—over 80% of the children adopted internationally were girls, and over 80% had congenital disabilities or illnesses.

Below is the full story.

Lannie said that many of the things she did later stemmed from 2002.

Lannie's Chinese name is Long Lan. She was born in 1970 in a rural area on the outskirts of Guangzhou. Her mother gave birth to five daughters, and she was the fourth. Mothers who didn't have sons were often ridiculed as "childless" back then.

The family was very poor, often without enough food to eat. Her father worked far from home for years, while her mother worked alone to feed five people, sometimes cutting rice late into the night.

Because of their dire situation, her mother wanted to find a good family to adopt her daughters. She thought it was better to be well-fed than to suffer from hunger with her. A childless couple, both teachers, was willing to adopt Lannie, but her father, unable to let her go, said they could adopt her only if her surname remained the same.

The couple didn’t agree, so her father brought little Long Lan back. Years later, her mother would still say, “We should have let you stay with them:

You might have had a chance to go to university.

Long Lan's eldest sister was also adopted for several years. When she was about six or seven years old, she accidentally killed a duck while herding them. Her father still kept in touch with the family that adopted her, and during a visit, the eldest sister, who knew who her biological father was, followed him home, fearing punishment for her mistake.

That family later adopted another girl, who eventually got into college. Over the years, the eldest sister didn't live well, and the mother always regretted not leaving her with that family, thinking she would have been better off.

Her second sister also almost got adopted, but the adopting family lived far away in Xinjiang, and she didn't want to go, so in the end, she stayed. Thus, the five sisters grew up together.

In 1987, Long Lan graduated from middle school and, after some detours, ended up working at a gift shop in Shamian, Guangzhou. The U.S. Consulate General in Guangzhou was located in Shamian at the time. In the early 1990s, international adoption from China officially began. Some foreign adoptive families, when arranging visas for their adopted children, had to stay in cities where their country's consulate was located for at least a week. Those in Guangzhou often stayed at the White Swan Hotel, and during their free time, they would shop near the consulate, usually buying souvenirs.

With the experience she accumulated from her job, at the age of 26, Lan Ni opened a small gift shop nearby. Most of her customers were foreigners who had adopted children from China. She thought these foreign families were very loving, but she didn't understand the children's biological parents:

How could they bear to abandon their children?

In early 2002, Lan Ni’s shop received a visit from an American single father who came to Guangzhou to arrange a visa for his second adopted daughter. A few months later, he contacted Lan Ni from the U.S.

He said that the orphanage where his daughter had been previously wanted to buy air conditioners for the children. He had raised some funds and wanted to bring them to China, asking Lan Ni to act as a translator.

During that trip, he also wanted a color photo of his second daughter as a baby. When he had adopted her, the fee list included a $50 notice fee, which the orphanage said was for a notice posted when the child was found. He wanted a copy of it, but they said there were regulations prohibiting giving it to adoptive families.

Feeling disappointed, they decided to search for the original notice. After much searching, they finally found it in a warehouse hidden in an alley. It was from a newspaper they couldn't find at any newsstand—"Guangdong Public Security News."

They thought other adoptive families might also want to keep such notices, so they bought a large stack of newspapers.

Two years later, Lan Ni and the man got married. Her habit of collecting old newspapers has continued ever since.

1

According to the regulations of the Ministry of Civil Affairs, when welfare institutions put abandoned babies or children up for adoption, the civil affairs department must publish notices in provincial-level newspapers to search for the biological parents. If the parents or other guardians do not claim the child within 60 days, it is considered that the biological parents cannot be found.

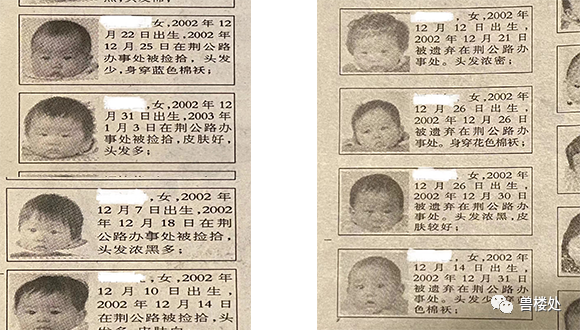

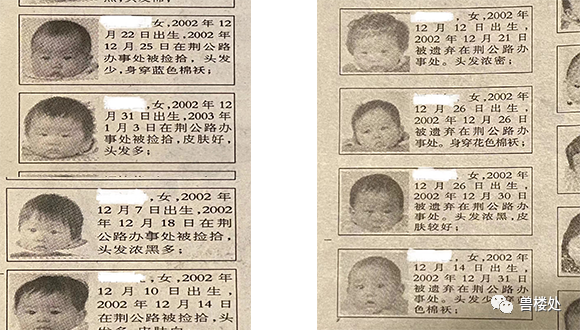

Most of these search notices are published in the legal or social sections of newspapers, and some appear in the margins. Early notices were purely text. In Guangdong Province, notices started including photos of the babies around 2001, while in Hunan and Jiangxi, they began including photos in 2003.

Most of the families searching for their lost children were poorly educated, some were even illiterate, and their small social circles made newspapers inaccessible. Meanwhile, the children's names were often changed by the orphanages, and their birth dates were estimated.

After 2002, Lan Ni also went to the United States. Every time she returned to China, she visited local libraries to search for local newspaper notices, spending two or three days in each city collecting scanned copies of these notices.

She has collected notices from more than 50 cities, from the "Yangcheng Evening News," "Hunan Daily," "Changjiang Business Daily," to the "Yunnan Daily" and "Anhui Youth Daily," among others.

Some small newspapers weren't even available in libraries. She had to search the streets and ask around. After finding the newspaper offices, she would buy several years' worth of newspapers in one go, selecting those that published the notices and filling her suitcase.

Her trips home typically lasted about a month. After collecting the newspapers, Lan Ni would rest for a week and spend time with her mother. Over seventeen or eighteen years, she visited 21 provinces and the cities of Beijing, Tianjin, and Shanghai. Each trip left her feeling as if she had been seriously ill.

At first, she simply thought this information was important. Other adoptive families didn’t have the means to find it, and newspapers were regularly destroyed, so they might miss it forever.

As she collected more notices, she began to notice certain details.

For instance, each child only appeared once in the newspaper, and she never saw repeated international adoption notices. Additionally, there were many older boys' found notices, with some boys being six, seven, or even eleven years old, stating that they were found at a square or market, with no mention of any health issues. She thought, for such an older child, surely they would know their family members' names.

Why were they sent to the orphanage and then adopted abroad?

The notices began to reveal more and more information.

2

After returning to the U.S., Lanny entered each child’s information into the computer: date of birth, pick-up date, pick-up location, and name at the time of adoption.

The original records were also preserved. In the warehouse, there were seven filing cabinets, each with six drawers per column, and most of the newspapers were well-preserved.

Because there was so much collected information, entering all the data into the computer has yet to be completed. The entries with the highest numbers:

Guangdong Province has 30,233 entries, Jiangxi has 23,959, Hunan has 18,876, Guangxi has 13,338.

Additionally, Hubei has 8,555 entries, Anhui has 7,584, Jiangsu has 7,241, Henan has 7,172, Chongqing has 7,030, and Zhejiang has 2,304. These ten provinces alone have over 126,000 data entries.

Many notices seem to describe random, one-off events. For instance, some of the children were listed as found at the entrance of a nursing home.

However, when the pick-up dates and locations from the notices were aggregated into big data, some coincidences emerged.

For example, between March and August 2005, 16 newborns were successively found at the entrance of a nursing home in Shangrao, Jiangxi. When they were adopted, they all had the surname:

"Ling."

Two years later, a similar event occurred. Between November 2007 and February 2008, at the same nursing home entrance, a newborn baby was found every ten days, on average.

Why did these families, without prior coordination, all choose to abandon their children in the same place?

There were even more concentrated occurrences. Between December 14 and December 31, 2002, seven newborns were found at the Jinggong Road office in Fuzhou.

The data from different regions had distinct patterns.

For instance, in Guizhou, many children were reported to have been found at the entrance of specific homes. Some later found, after a successful search for their birth families, that they had actually been taken directly from those households. In Hunan, the reports frequently mention government offices, clinics, and nearby schools as the pick-up locations.

When looking at the Jiangxi data, the locations often include the entrance of welfare institutions, civil affairs bureaus, and occasionally streets and hospitals. However, in some small towns, the family planning office and civil affairs bureau are often housed in the same building as the town government. In other words, many addresses are actually the same place.

In 2005, a noticeable shift occurred.

Before this, 80-90% of the children in the adoption notices were girls, usually between 9 months and 2 years old.

After 2005, boys accounted for around 40%, and there was an increasing number of older children, even up to 14 years old.

The proportion of children with congenital diseases also increased. Overall, the total number of adoptions has gradually decreased.

The current data includes 36 children picked up in Quan County, Guangxi, at least four of whom were found near family planning offices.

Deng Xiaozhou’s family in Quanzhou said their son was born in 1989 and taken away at around one year old. According to Lanny’s search experience, most children adopted by foreign families were born after 1991.

With tens of thousands of data pieces coming together, an enormous puzzle is slowly taking shape.

3

Lanny’s family has adopted three children from China.

The eldest daughter was adopted by her husband and his ex-wife in 1998, and the second daughter was adopted by her husband during his single years, both from welfare institutions in Guangdong.

In 2005, after they were married, they adopted their third daughter from a welfare institution in Henan.

At that time, she only knew that these children had no parents and wanted to give them a home. Becoming a mother seemed like a wonderful thing.

Many countries allow international adoption, from Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, Bulgaria, to several African nations. Overseas families often consider China's process to be relatively straightforward, with clear fees.

The early 1990s marked a turning point for the flow of children in Chinese welfare institutions. In 1991, China became one of the largest sending countries for adoptions, establishing international adoption agreements with 17 countries.

Official statistics show that over 150,000 Chinese children were adopted by overseas families.

For foreign families to enter the adoption process, they first need to contact an adoption agency in their home country, provide proof of income, a criminal background check, a health certificate, pay the necessary fees, and submit an application to their government. After approval, the documents are notarized and sent to China for review. Once the application is submitted, the wait time is typically between one and two years.

In April 1992, the Adoption Law was enacted, allowing foreigners to adopt children in China according to the law.

In 2003, the Ministry of Civil Affairs issued the Several Provisions on the Work of Intercountry Adoptions by Social Welfare Institutions. According to these provisions:

Children adopted internationally must be orphans or abandoned children.

After receiving proof submitted by welfare institutions nationwide, the China Adoption Center in Beijing matches the children with the information provided by foreign adoption agencies, including photos and family details.

After waiting for at least a year, foreign families receive a document from the China Adoption Center:

We have matched you with a child from a certain welfare institution, and the child’s name and birthdate are provided.

From that day, the family begins waiting for their travel notice.

Before departing, adoptive families are required to exchange currency into Chinese yuan because they must sign a voluntary donation agreement: Party B voluntarily donates 35,000 yuan to Party A.

Upon arrival, the families usually go to the provincial civil affairs office to complete the formalities. At that point, the welfare institution hands the child over to the adoptive parents.

After the handover, the welfare institution provides a certificate of abandonment and the child's passport. A few children also have a birth certificate or, if the birth parents left one, a note. These documents are often preserved and given to the adoptive family as a copy.

Once the visas are processed, the children board a flight with their adoptive families to a foreign land.

Back in the United States, Lannie entered each child's information into the computer. Birth date, pick-up date, pick-up location, name at the time of adoption.

The original data is also preserved. There are 7 filing cabinets in the warehouse, each with a column of 6 drawers, and most of the newspapers are well preserved.

Because there is too much information collected, the project of entering all the data into the computer has not been fully completed yet. The provinces with the most entries:

Guangdong Province has 30,233 entries, Jiangxi has 23,959 entries, Hunan has 18,876 entries, Guangxi has 13,338 entries.

Additionally, Hubei has 8,555 entries, Anhui has 7,584 entries, Jiangsu has 7,241 entries, Henan has 7,172 entries, Chongqing has 7,030 entries, Zhejiang has 2,304 entries. These ten provinces alone have a total of 126,000 data entries.

Many announcements look like very normal sporadic events. For example, some children are noted as being picked up at the entrance of a nursing home.

But once the pick-up dates and locations from the announcements are aggregated into big data, some coincidences become apparent.

For example, between March and August 2005, 16 newborns appeared one after another at the entrance of a nursing home in Shangrao, Jiangxi. When they were adopted, they all had the surname:

"Ling".

Two years later, similar events occurred again. From November 2007 to February 2008, at the same nursing home entrance, an average of one infant under one month old was found every ten days.

Why did these families, without prior arrangement, abandon their children in the same place?

There are even more concentrated cases. From December 14 to 31, 2002, seven newborns were found at the "Jinggong Road Office" in Fuzhou within half a month.

Data from different regions has its own style.

For example, in Guizhou, many children's information notes that they were picked up at someone's doorstep. Some successful reunions revealed that the children were directly taken from these households. Hunan prefers to write the town government entrance, the health clinic entrance, and the neighboring middle school entrance.

Opening Jiangxi's data, you will continuously see welfare home entrances, civil affairs bureau entrances, and occasionally street and hospital entrances. However, in some small towns, the family planning office and the civil affairs bureau are often in the same building as the town government. In other words, many addresses are actually the same address.

In 2005, a very obvious turning point appeared.

Before this, 80-90% of the children in international adoption announcements were girls, usually between 9 months and 2 years old.

After 2005, boys gradually accounted for about 40%, and more and more children were 7-8 years old, or even nearly 14 years old.

The proportion of children with congenital diseases also increased. The overall data volume decreased year by year.

In the existing data, there are 36 children picked up from Quanzhou County in Guangxi, and at least 4 of them were noted as being picked up at the Quanzhou family planning department.

The Deng Xiaozhou family in Quanzhou said their son was born in 1989 and was taken away around one year old. According to Lannie's experience in searching for relatives, Chinese children adopted by foreign families were generally born in 1991 or later.

A huge puzzle, with hundreds of thousands of pieces coming together, is gradually revealing its full picture.

3

Lannie's family adopted three Chinese children in total.

The eldest daughter was adopted by her husband and his ex-wife in 1998, the second daughter was adopted by her husband during his single period, both from Guangdong welfare homes.

In 2005, after they were married, they adopted their third daughter from a welfare home in Henan.

At that time, she only knew that these children had no parents to raise them, and she wanted to give them a home. Becoming a mother seemed like a very beautiful thing.

Many countries allow international adoptions, from South Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, Bulgaria, to various African countries. Overseas families generally believe that China's procedures are relatively simple and the costs are clear.

The early 1990s marked a watershed in the flow of children in Chinese welfare homes. Starting in 1991, China became one of the largest sending countries for adoptions, establishing cross-border adoption cooperation with 17 countries.

Official figures show that more than 150,000 Chinese children have been adopted by overseas families.

Overseas adoptive families must enter the adoption process. First, they need to contact an adoption agency in their own country, provide proof of annual income, proof of no criminal record, health certificate, etc., pay fees, submit an application to their government department, undergo a background check, and after approval, notarize the documents and send the file to China for review. After submitting the application, it usually takes one to two years or more.

In April 1992, the "Adoption Law" was implemented. Foreigners could adopt children in China according to this law.

In 2003, the Ministry of Civil Affairs issued the "Regulations on the Work of International Adoption by Social Welfare Institutions". According to these regulations:

For international adoption, the child must be an orphan or abandoned child.

After receiving the certificates submitted by welfare homes across the country, the China Adoption Center in Beijing would match the adoptive families provided by foreign adoption agencies based on their photos and information.

After at least a year or more of procedures, overseas families would receive a document from the China Adoption Center:

We have matched you with a child from a certain welfare home, named so-and-so, born on such-and-such date.

From this day on, the family would start waiting for the travel notice.

Before departure, the adoptive family needs to exchange for RMB cash because they have to sign a voluntary donation agreement: Party B voluntarily donates 35,000 yuan to Party A.

After the overseas adoptive family arrives, they usually go to the provincial civil affairs department to complete the procedures. There, the welfare home hands over the child to the adoptive parents.

After the handover procedures are completed, the welfare home provides the child's abandonment certificate and passport. A few children have birth certificates when they enter, and if the biological parents left a birth note, it is sometimes preserved and a copy is given to the adoptive family.

After the visa is processed, these children follow the adoptive family onto a flight to a foreign country.

4

The background of adopted children is often stated as follows—

Certificate

Shao Yanni (female) was born on April 8, 1999, and was found abandoned at the entrance of No. 23 Dongfeng Road, Shaoyang City on May 6, 1999, picked up by Shaoyang resident Zeng Yunxiu, and sent to our institute by Shaoyang City Guangchang Police Station on May 6, 1999. To date, her biological parents and other relatives have not been found.

Shaoyang Children's Welfare Institute

October 27, 1999

Certificate

Shao Fugao (female) was born on February 18, 2002, and was found abandoned at the entrance of No. 155 Baoqing Middle Road, Shaoyang City on February 18, 2002, picked up by Shaoyang resident Zhang Lanxiu, and sent to our institute by Shaoyang City Guangchang Police Station on February

These children who grew up abroad learn about their origins from the pick-up certificates as they grow older. A pick-up location with a house number and a named picker make the facts seem solid.

Some children want to find their birth parents, so Lannie received many adoption documents sent to her by these children. She found that some certificates did not match the information in the announcements published in newspapers.

For example, in the case of Shao Yanni mentioned above, the newspaper announcement stated that her pick-up location was the Civil Affairs Bureau of Longhui County, but the certificate received by the adoptive family indicated the pick-up location was in Shaoyang City.

Some of the children adopted overseas had been temporarily placed with other families by their birth parents and were eventually separated due to fines.

If very lucky, the adoption information accurately recorded the original household, and the child might still be able to find the former foster family after many years.

Otherwise, before DNA matching became available, the process was often full of twists and turns. "Shao Yanni," originally named Yang Ye, is the biological daughter of Yang Nengshan, who lives in Group 7, Longshi Village, Tantou Town, Longhui County. The Yang family never stopped searching for their daughter.

According to Yang Nengshan's account, in 1999, while he was working in Guangzhou, personnel from the town's family planning office, along with more than thirty unidentified individuals, surrounded his home and took Yang Ye from his wife's arms.

In a 2018 phone recording, they questioned the person in charge at the time, who firmly stated: Yang Ye was not sent away; she was still in Tantou.

DNA has already matched another girl with her biological parents. "Shao Fugao," originally named Liu Huan, is the second child of Liu Qibo, from Group 7, Niejia Village, Hexiangqiao Town.

In 2002, after Liu Huan was sent away by the town's family planning office, she disappeared without a trace. Liu Qibo spent over a decade borrowing money to search for her. In 2013, he was sentenced to four years in prison for fraud.

5

When Xiaoyu left a welfare home in Jiangxi in 2002, she had a growth report. The report told her adoptive family that the girl was wearing a cotton-padded jacket and an orchid apron, with a baby hat on her head when she was found by villagers.

A red slip of paper recorded her birth date.

What impressed Xiaoyu's caregiver was that she laughed loudly, loved listening to music, responded quickly, and was very sociable.

Although she did not understand Chinese, Xiaoyu's adoptive mother kept these few A4 sheets separately.