Lin Biao:The Rise and Fall of a Military Genius (Part 2)

Early Years of the People’s Republic of China

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China, Lin Biao held various positions including Chairman of the Central South Military and Political Committee (later changed to the Central South Administrative Committee), Commander of the Central South Military Region and the Fourth Field Army, Vice Chairman of the Chinese People’s Revolutionary Military Committee, Vice Premier of the State Council, and Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission of the Chinese Communist Party. He was also Vice Chairman of the First, Second, and Third National Defense Committees and a member of the Central Committee and the Political Bureau of the Seventh and Eighth Central Committees of the Chinese Communist Party.

After the establishment of the People’s Republic, Lin Biao remained aloof and never involved himself in the circle of generals and marshals. “He did not visit others, did not receive guests, and most of the people who came to visit him were turned away by Ye Qun” [81].

Rising to the Standing Committee of the Political Bureau

On June 25, 1950, the Korean War broke out. In October, at an expanded meeting of the Central Secretariat, Mao Zedong proposed that Lin Biao lead the army into Korea. Despite repeated persuasion, Lin Biao declined, citing illness, and consistently opposed sending troops, arguing that “the country has just been liberated, and the victory was hard-won, achieved through the blood and sacrifice of countless martyrs. We are not as strong as the United States and cannot afford to set ourselves on fire” [82]. Lin Biao also believed that the Korean War was instigated by Stalin, “The United States has already informed us that if China does not send troops to Korea, it will immediately establish diplomatic relations with China. This may be a conspiracy, but it is also an opportunity” [84]. Afterward, Lin went to the Soviet Union to “recuperate.” During the fifth campaign to resist U.S. aggression and aid Korea, the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army entered a stalemate in Korea. Around June 18, 1951, Lin Biao returned to China to replace Zhou Enlai in presiding over the work of the Military Commission, but was soon replaced by Zhou again [73]. On November 5, Lin Biao was added as Vice Chairman of the Central Military Commission.

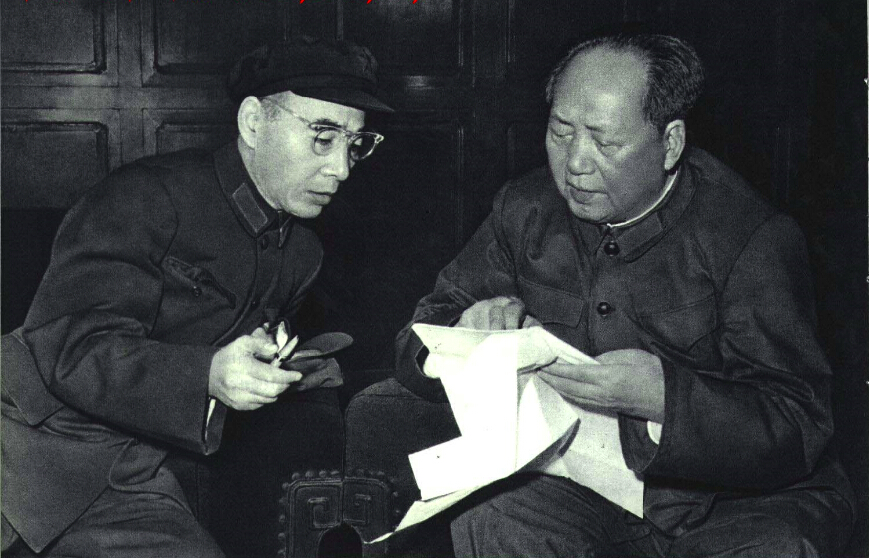

In 1954, Lin Biao was appointed Vice Premier of the State Council (ranked after Chen Yun and before Deng Xiaoping) and Vice Chairman of the National Defense Commission. On April 4, 1955, he was elected to fill the vacancies left by Ren Bishi and Gao Gang, becoming a member of the Central Political Bureau along with Deng Xiaoping. On September 27, Lin Biao was awarded the rank of Marshal, but he and Liu Bocheng did not attend Mao Zedong’s award ceremony [10]. From September 15 to 27, the Eighth National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party was held, where Mao Zedong was unanimously re-elected as Chairman of the Central Committee, with the sole vote against him being his own vote for Lin Biao [16]. On the 28th, Lin Biao was elected as a member of the Central Political Bureau at the First Plenary Session of the Eighth Central Committee. In May 1958, Lin Biao attended the second session of the Eighth National Congress and the Fifth Plenary Session of the Eighth Central Committee. On the 25th, at the Fifth Plenary Session, Mao proposed the election of Lin Biao, who had been recuperating for a long time, as Vice Chairman of the Central Committee and Standing Committee of the Political Bureau, which was approved. From then on, Lin entered the highest echelon of the Chinese Communist Party, ranking sixth [57].

Despite his promotion, Lin Biao did not wield significant power, “During this period, although his positions continued to rise, he basically did not work in his posts, living a reclusive life and rarely appearing in public or participating in social activities. His main focus was on recuperation” [10].

The Lushan Conference of 1959

From July 2 to August 1, 1959, an expanded meeting of the Central Political Bureau was held in Lushan, Jiangxi. On July 25 [h], Lin Biao was summoned to Lushan by Mao Zedong [85]. Like most attendees, Lin harshly criticized Peng Dehuai. However, when Peng was attacked by Mao for Lin’s letter before the Hui Li meeting, Lin clarified, “I wrote to the Central Committee at that time, asking Mao, Zhu, and Zhou to leave their military command posts and let Peng Dehuai command the operations. This was not discussed with Peng Dehuai beforehand and had nothing to do with Peng Dehuai” [86][87][88]. After the meeting, Peng Dehuai and others were overthrown. On September 17, Mao Zedong proposed that Lin Biao replace Peng as Minister of National Defense. On the 26th, Lin Biao and He Long became the first and second Vice Chairmen of the Central Military Commission [86][87]. From this point, Lin Biao began to place his subordinates Li Zuopeng, Qiu Huizuo, Jiang Tengjiao, Huang Yongsheng, and others in key positions within the military [89][90][91][92][93][94].

Promoting Modernization of National Defense

In February 1960, Lin Biao linked Mao Zedong’s 1939 inscription for the Anti-Japanese Military and Political University: “Firm and correct political direction, simple and hard-working work style, flexible and mobile strategy and tactics” and “Unity, tension, seriousness, liveliness” into “Three-Eight Work Style.”

During this period, Lin Biao insisted that military construction must develop towards high technology and vigorously supported military scientific research. On February 27, 1960, at the Sixth Expanded Meeting of the Central Military Commission, Lin Biao proposed: “1. Future wars will be fought with buttons. 2. The most urgent and important thing in war preparations, which should be prioritized, is solving the issue of weapons, especially developing advanced weapons. 3. Future wars will not only rely on infantry but on the air force and missiles. The role of the air force on the battlefield will become increasingly significant, and at certain times it may become a decisive means. The air force should be given priority in development.” He emphasized the development of “missiles as the main focus, guided by the principle of developing electronic technology,” and proposed a clear plan for developing advanced national defense technology. He also called for the significant development of the air force, navy, and special forces based on establishing a complete modern national defense system [95].

In October and November 1961, Zhang Aiping reported to Lin Biao that many central leaders demanded the termination of the atomic bomb project. Lin instructed, “The atomic bomb must be developed and it must explode, even if it has to be fired with wood” [96].

The 7,000 Cadres Conference

From January 11 to February 7, 1962, an expanded Central Work Conference (commonly known as the 7,000 Cadres Conference) was held to summarize the errors of the Great Leap Forward and hope for an end. State Chairman Liu Shaoqi and others reviewed the issues of the three red flags, with Liu constantly interjecting while Mao Zedong was speaking [97]. Amid the voices of review, Lin Biao, on January 29, abandoned the prepared speech by the Military Commission Office [54] and spoke off the cuff:

Facts have proven that these difficulties, in some aspects and to some extent, are precisely because we did not follow Chairman Mao’s instructions, warnings, and thoughts. If we had listened to Chairman Mao and understood his spirit, the detours would have been much fewer, and today’s difficulties would have been much smaller. I feel that among our comrades, there are often three kinds of thoughts: one is Chairman Mao’s thought, one is leftist thought, and one is rightist thought. It has been proven both at the time and afterward that Chairman Mao’s thought is always correct. However, some of our comrades cannot fully understand Chairman Mao’s thoughts and always pull problems to the left and deviate to the left, saying that they are executing Chairman Mao’s instructions but in reality, they have deviated.

Most of the participants believed that Lin Biao’s speech was excellent, and Mao Zedong immediately applauded and praised (the only commendation), asking Liu Shaoqi to record and organize it. On March 20, Mao instructed Tian Jiaying and Luo Ruiqing: “I have read this document. It is an excellent and weighty article, and I am very pleased to see it.” Mao also advised Luo to learn from Lin [97].

Lin Biao’s speech, which deviated from the writing team’s draft and was spontaneously given based on a rough outline, was later regarded by some commentators [who?] as premeditated and unique [98].

He said: “The three red flags proposed by our Party—the General Line, the Great Leap Forward, and the People’s Commune—are correct. They are creations of the Chinese revolutionary development, creations by the people, and creations by the Party. If we have any spirit of seeking truth from facts, we cannot ignore the significant setbacks the national economy has suffered in recent years and their relationship to the three red flags. For example, the ‘General Line’ has always emphasized that ‘speed’ is the soul, only emphasizing ‘fast’ while neglecting good and economical results. The ‘Great Leap Forward,’ as the name suggests, also emphasizes rapid development. Because the targets set by the central government were too high, local officials began to exaggerate. The exaggerated figures were then accepted by the central government, and economic plans were constructed based on these inflated numbers, which in turn guided local work, leading to a vicious cycle that ultimately resulted in a complete economic collapse. In agriculture, people had no food to eat, and in industry, it was a waste of resources. It was obvious to anyone with clear eyes that this was not a ‘Great Leap Forward’ but more like a Great Retreat.” Du Runsheng later recalled: “At that time, we felt that Lin Biao stood up and spoke against interference, giving our Party a sense of security—someone even said so back then.”

The Five Years of the Cultural Revolution

The Only Vice Chairman of the Central Committee

According to the Chinese Communist Party’s official account, on November 30, 1965, Lin Biao had Ye Qun falsely accuse Luo Ruiqing of “usurping military power and opposing the Party” and “opposing the emphasis on politics,” which Mao Zedong believed, leading to Luo’s downfall. However, Lin Biao’s daughter, Lin Liheng, and writer Shu Yun believed this had nothing to do with Lin Biao and was a prelude to Mao’s move against Liu Shaoqi. On May 18, at an expanded meeting, Lin Biao gave a long speech, discussing instances of coups in ancient and modern times, claiming that someone within the central government was planning a coup, and began promoting personal worship, saying, “Chairman Mao is a genius, every word of Chairman Mao is truth, one sentence of his surpasses ten thousand of ours,” and “his words are our guidelines for action, anyone opposing him will be condemned by the entire Party and the entire nation.”

On August 1, 1966, the 11th Plenary Session of the 8th Central Committee was hastily convened under Mao Zedong’s leadership. On the 4th and 5th, Mao twice requested Lin Biao to return to Beijing to attend the session, but Lin said he was ill and could not attend, and Premier Zhou Enlai personally went to invite Lin. On the morning of the 6th, Mao adjourned the meeting to “wait” for Lin (a method Mao later used when Ye Qun was absent). On the evening of the 6th, as soon as Lin arrived, Mao greeted him to discuss matters. On the 8th, the plenary session passed the “Decision of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution,” officially starting the Cultural Revolution. At Zhou Enlai’s suggestion, the session passed a resolution replacing Liu Shaoqi with Lin Biao as the sole Vice Chairman of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, and Lin’s ranking in the Standing Committee of the Politburo was elevated to second only to Mao. After Liu Shaoqi’s self-criticism at the plenary session, Lin approved and stood up to shake hands with him.

On the 13th, Lin Biao said at the central work conference:

Recently, I have felt very heavy-hearted. My work and my abilities are not matched, and I am unqualified. I expect to make mistakes. … The work assigned to me by the central government exceeds my level and ability. Despite my repeated requests to decline, now that the Chairman and the central government have decided, I have no choice but to comply with the Chairman’s and the Party’s decision, to give it a try, and strive to do well. I am also ready to hand over my responsibilities to more suitable comrades at any time.

Li Wenpu also stated that Lin Biao had expressed several times that he did not want to play such a role.

After Liu Shaoqi was overthrown, Lin Biao visited him and said, “Liu Shaoqi is the Vice Chairman of the Central Committee, Kuai Dafu’s opposition to Liu Shaoqi is actually opposition to the Party.” Later, Lin wrote on a report about the investigation of Liu by the central special case group: “I fully agree, and salute Comrade Jiang Qing for her outstanding leadership in the special case work and great achievements.” Some believed this implied that the special case had nothing to do with him.

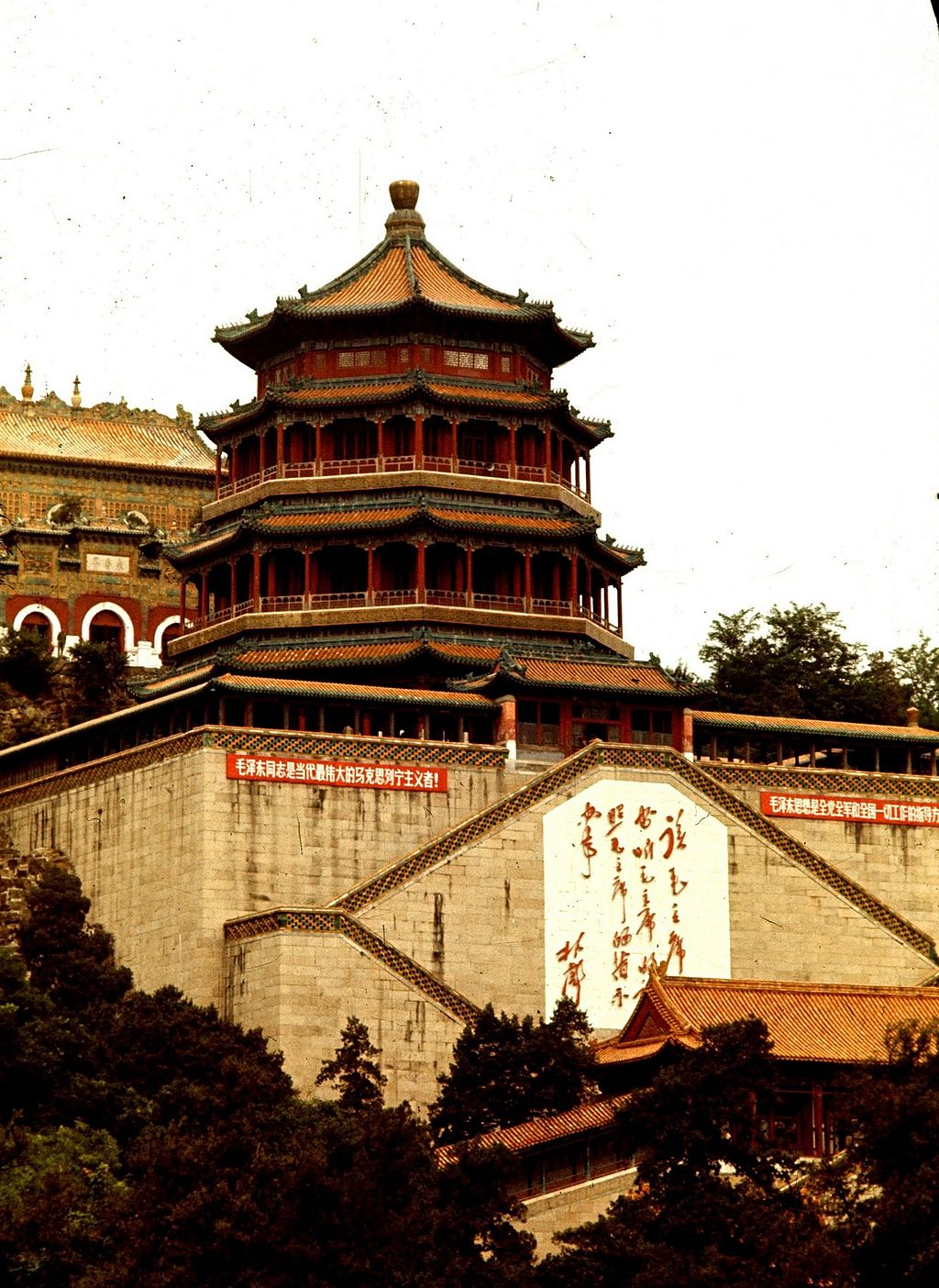

From August 18 to November 26, Mao Zedong met with Red Guards from all over the country eight times at Tiananmen Square to show support, and Lin Biao was present at each meeting, standing next to Mao. Lin shouted, “Whoever dares to oppose Chairman Mao will be condemned by the entire nation and the entire Party!” Lin Biao, “thin and pale due to poor health, did not want to accompany Mao Zedong in meeting the Red Guards, but had no choice, sometimes to the point of exhaustion. On one occasion, he almost couldn’t make it back after accompanying Mao to meet Red Guards at the Jinshui Bridge at the base of Tiananmen.”

On September 9, Lin Biao, as Minister of National Defense, appeared on the cover of the American edition of Time magazine, with the caption “China’s Nightmare” in the upper right corner of the photo. That month, Mao Zedong had Lin Biao read “The Biography of Guo Jia” from the “Records of the Three Kingdoms” and “The Biography of Fan Ye” from the “Book of Song.” Guo Jia was a meritorious official of Cao Cao who died at 38. Fan Ye was killed by Emperor Wen of Song for “treason.” Their relationship sounded the first alarm; Lin Biao, who had always been able to accurately predict the situation, was evidently aware of future events.

During the Cultural Revolution, unlike Mao Zedong’s verbal requests not to promote personal worship, on March 20, 1967, Lin Biao instructed at a meeting of senior military officers to stop the recently resumed publication of the “Quotations from Lin Biao” (which had been banned before). That summer, he stipulated that no publications should be released praising him, no calls for “Long live the health of Vice Chairman Lin,” and even had thousands of copies of the directive printed and distributed to ensure compliance. After he learned that a fight had erupted due to differing celebrations of his inscriptions, he stopped inscribing altogether.

The He Long, Yang Yu, and Fu Incident

On September 6, 1966, Lin Biao, entrusted by Mao Zedong, formally “warned” about He Long’s issue at a central military commission meeting, saying: “Since the military has carried out the Cultural Revolution, some people in various departments, branches of the military, and certain major military regions have reached out, attempting to create chaos to seize power amid the confusion. … Their main backstage supporter is He Long, so the Chairman said we must warn senior military cadres about He Long’s ambitions.” Several senior marshals present expressed support for Mao’s decision.

Writer Shu Yun believed that He Long, who had close ties with Liu Shaoqi, was also targeted by Mao, unrelated to Lin Biao.

On March 24, 1968, Lin Biao delivered a speech at a military cadre meeting, conveying the central government’s order from March 22: “The meeting was presided over by the Chairman himself. The meeting decided to remove Yang Chengwu from his position as acting chief of staff, arrest Yu Lijin, and remove Fu Chongbi from his post as commander of the Beijing Garrison.” Yang Chengwu, Yu Lijin, and Fu Chongbi were overthrown.

Becoming Mao Zedong’s Successor

On April 1, 1969, the Ninth National Congress of the Communist Party of China was held in Beijing, unprecedentedly including in the newly revised “Constitution of the Communist Party of China” the statement: “Comrade Lin Biao is Chairman Mao’s close comrade-in-arms and successor.” This controversial phrase was proposed by Jiang Qing during the Eighth Central Committee’s Twelfth Plenary Session on October 17, 1968, when discussing the draft Party constitution, and was ultimately passed after further study.

Writer Gao Wenqian summarized: “(Lin) was the idle second-in-command, pushing away as much as possible, avoiding getting involved in the big and small matters of the movement, never taking the initiative to express opinions. He described it as ’not troubling with big matters and not interfering with small ones,’ while Ye Qun summarized it as the ’three-no policy’—’no responsibility, no suggestions, no offense.’

This not only avoids suspicion from Mao Zedong but also allows one to appear detached and politically irresponsible. “Lin Biao painstakingly created an image of being politically ‘in line’ with Mao Zedong to mask his passive attitude in politics”[116].

Around September, Lin Biao met with the Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, Pham Van Dong, and the Minister of Defense, Vo Nguyen Giap. Regarding the Vietnam War, he repeatedly emphasized: “In the face of the powerful United States, your approach is to endure, and endurance means victory”[117].

Lushan Incident

During the Cultural Revolution, Lin Biao heavily relied on Huang Yongsheng, Wu Faxian, Li Zuopeng, and Qiu Huizuo. After Yang Chengwu’s downfall, these four controlled the Military Commission Office and effectively controlled the military. In March 1970, Mao Zedong repeatedly opposed the establishment of a president in the draft constitution, facing collective opposition from Lin Biao, Zhou Enlai, Kang Sheng, and other Politburo members[118][119][120]. On August 13, 1970, at the draft constitution group discussion meeting, Wu Faxian had a fierce argument with Zhang Chunqiao over whether to include the phrase “Mao Zedong Thought is the guideline for all work of the State Council” in the draft constitution. Zhang Chunqiao sarcastically criticized Lin Biao by praising the Soviet Union’s “Khrushchev’s genius in creatively and comprehensively developing Marxism,” which led to Wu Faxian’s strong protest. This issue escalated to Lin Biao, drawing his attention and leading to a public conflict between Zhang Chunqiao and Lin Biao’s faction.

From August 23 to September 6, the Ninth Central Committee’s Second Plenary Session (the Third Lushan Meeting) was held in Lushan, Jiangxi. Lin Biao spoke first and criticized Zhang Chunqiao for “using Chairman Mao’s great humility to oppose Chairman Mao” without naming him. This conversation became the fuse for the entire Lin Biao incident. In subsequent group discussions, Wu Faxian, Qiu Huizuo, and others, led by Chen Boda and Wang Dongxing, openly criticized Zhang Chunqiao and gained the support of most committee members. Many central committee members mistakenly believed that Mao Zedong had abandoned Zhang Chunqiao and actively pledged allegiance to Mao and Lin Biao. Xu Shiyou even wrote to Mao requesting that Zhang Chunqiao be sent to labor reform[118][121]. This provoked Mao Zedong’s fury, leading to the beginning of the “Criticize Chen and Rectify” movement and the subsequent split between Mao and Lin Biao[122]. After the meeting, Mao Zedong used tactics such as “throwing stones,” “adding sand,” and “digging the wall” against Lin Biao’s main office, the Military Commission Office. Lin repeatedly sought to meet with Mao but was unsuccessful, and their relationship deteriorated sharply[54][123].

Whether Lin Biao consulted Mao Zedong before his speech became a focal point. Officially, especially Mao Zedong, it was believed that Lin Biao had not consulted Mao (Mao Zedong’s southern inspection speech) and that it was a surprise attack; however, Chen Boda, Qiu Huizuo, Wu Faxian, and Li Zuopeng all testified that Lin Biao had consulted Mao before his speech, and Mao Zedong had requested that Lin Biao not name names during his speech (Zhang Chunqiao).

Mao-Lin Split

After the Ninth Central Committee’s Second Plenary Session, Mao Zedong launched the “Criticize Chen and Rectify” campaign, directly targeting the four members of the Military Commission Office and Ye Qun. By April 1971, the five had written multiple self-criticisms to Mao Zedong. Mao Zedong’s attitude fluctuated; he sometimes said “the issue won’t go down (Lushan)” and sometimes referred to it as a “sudden attack” and “deceiving more than 200 central committee members.” Mao Yuanxin even used the harsh term “failed military coup” (though Wu Faxian and others believed this term was not invented by Mao Yuanxin[124]). Finally, at the Politburo meeting in April, Mao Zedong announced that their self-criticisms were “finished” here. However, after a brief calm of five months, in August 1971, Mao Zedong secretly embarked on a southern inspection tour, traveling through various provinces and cities, and publicly exposed his conflict with Lin Biao, announcing a “tenth line struggle” to prepare for the removal of Lin Biao[125]. Mao Zedong instructed Liu Feng, Commander of the Wuhan Military Region, to keep the conversation confidential but also said it could be disclosed to the Standing Committee[126]. Liu Feng did not respond clearly but eventually informed Qiu Huizuo, and the information was passed to Lin Biao. Lin Liguo’s “small fleet” attempted to counterattack in panic.

From March 22 to 24, 1971, according to official CCP accounts, Lin Biao, Ye Qun, and Lin Liguo, Zhou Yuchi, and Yu Xinye devised an armed coup plan, named the “571 Project Summary”[127]. From September 8 to 11, Lin Liguo and Zhou Yuchi conveyed Lin Biao’s orders to Jiang Tengqiu, Wang Fei, and other key members of the “联合舰队” (Joint Fleet), specifically deploying the assassination of Mao Zedong. Mao was alerted to this and decided to suddenly change his southern tour itinerary, taking the train back to Beijing early, and accelerating without stopping along the way, ultimately returning to Beijing safely[128].

Escape and Plane Crash

At 3:00 PM on September 12, Mao Zedong arrived at Fengtai Station and met with Wu Zhong and others. Except for Zhou Enlai and others, central committee members in Beijing were unaware of Mao Zedong’s sudden return. That afternoon, through unknown means, Lin Liguo learned of Mao Zedong’s return to Beijing and took the 256 Trident from the western suburbs airport back to Shanhaiguan. That night, Lin Liheng reported to the 8341 Unit that Ye Qun intended to hijack Lin Biao. This news reached Mao Zedong, alerting Zhou Enlai. Zhou Enlai then spoke with Ye Qun, inquiring about the plane, advised Lin Biao not to fly at night, and mentioned going to Beidaihe to visit the Vice Chairman.

At 11:00 PM, Lin Biao, Ye Qun, Lin Liguo, and others suddenly left by car from Beidaihe. Guard Li Wenpu jumped from the car and was injured. At this time, Zhou Enlai notified Wu Faxian to go to the western suburbs airport to command, while Li Zuopeng conveyed Zhou Enlai’s instructions to prevent the plane from taking off (though Li Zuopeng later implied that Zhou Enlai did not intend to prevent the plane from taking off[129]). The car arrived at Shanhaiguan Airport via the national highway, and Lin Biao and others boarded the plane. With the lights off and navigation closed, the plane took off forcibly without proper positioning. The plane initially headed toward Datong and then turned towards Mongolia, eventually crashing in Wuduliang, Mongolia, for unknown reasons, with all on board killed[130][131].

After Lin Biao’s death, his body was hastily buried at the site by the Chinese Embassy in Mongolia. After being discovered by Soviet intelligence agents, the body was exhumed, and the skull was sent to the Soviet Union for examination, confirming that the deceased was undoubtedly Lin Biao. Lin Biao’s remains have yet to be returned to China.

Aftermath

After Lin Biao’s death, following Mao Zedong’s instructions, the relevant personnel dealt with various books found in Lin Biao’s home, which contained Lin Biao’s words:

He first fabricates a “your” opinion for you, and then refutes your opinion. This is a common tactic of Lao Dong; pay attention to this trick in the future.

He worships himself, has self-superstition, adores himself, and takes credit for himself while blaming others.

He should be taken care of in such a way that he has no need for small helpers; if every initiative and achievement is pointed out fairly and actively, he will naturally lose his sharpness.

Whoever does not lie will collapse.

The Great Leap Forward, relying on fantasy and reckless actions, was a losing business, going to extremes, destroying personal initiative. Absolute negation of the Soviet Union is wrong.

Among all the myriad affairs, this is the greatest: self-discipline and restoration of propriety[132].

On November 14, 1971, Mao Zedong issued copies of the so-called “571 Project Summary” allegedly created by Lin Biao to county and brigade-level party and government cadres[133]. The excerpts from the house search were later included in the “Criticize Lin and Criticize Confucius” materials and made public[134], exposing Lin Biao’s opposition to Mao Zedong.

In January 1972, during Chen Yi’s memorial service, Mao Zedong stated, “Lin Biao was opposed to me. If Lin Biao’s conspiracy had succeeded, it would have eliminated us old people!”[135]

In September 1973, Mao Zedong remarked during a meeting with foreign guests: “Qin Shi Huang was the first famous emperor of China’s feudal society, and I am also Qin Shi Huang. Lin Biao criticized me as Qin Shi Huang. China has always been divided into two factions, one praising Qin Shi Huang and the other condemning him. I support Qin Shi Huang and do not support Confucius” [136]. The “Criticize Lin, Criticize Confucius” movement began in January of the following year.

Lin Biao’s Anti-Party Clique Case

After Lin Biao’s death, Huang Yongsheng, Wu Faxian, Li Zuopeng, and Qiu Huizuo had not yet been removed from their positions and even collaborated with Zhou Enlai in tracking and handling the incident involving Lin Biao’s aircraft. Ten days later, on September 24, Zhou Enlai, acting on Mao Zedong’s orders, lured the four into a political bureau meeting at the Great Hall of the People. They were transferred to a military camp in the suburbs of Beijing for investigation. At the 10th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 1973, a decision was made to expel the four from the party permanently as members of Lin Biao’s faction.

After Lin Biao’s downfall, besides the fall of Lin Biao’s “small fleet” and “large fleet,” many people from the former Red Army’s First Front and the Northeast Fourth Field Army and Air Force systems were implicated. Additionally, Jiangxi Revolutionary Committee Secretary Cheng Shiqing, Zhejiang Province Revolutionary Committee Secretary Chen Liyun, Wuhan Military Region Commander Liu Feng, and even the suicide of Public Security Minister Li Zhen, as well as Central Committee Vice Chairman Li Desheng, were also impacted to varying degrees [137].

After the downfall of the Gang of Four in 1976, the four were not released but were instead transferred to Qincheng Prison to continue serving their sentences. In 1980, they were sentenced as principal members of Lin Biao’s counter-revolutionary group.

Criticism of Lin Biao in the Later Stages of the Cultural Revolution

Lin Biao ended his political career with a sudden flight, and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China took measures to keep it confidential, strictly prohibiting any leaks in the short term. After his death, according to student autobiographies from that time, the authorities initially maintained a pretense that Lin and Mao were still cooperating, but as foreign media reports emerged and Lin did not appear for a long time, the domestic public gradually learned the news. From 1973 onward, Mao Zedong initiated a struggle to criticize Lin Biao. At the 10th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, Lin Biao’s faction members were expelled from the party, and Lin Biao was labeled a “traitor” and a “traitor to the party and country” [138].

Later, Lin Biao and Chen Boda were directly associated, leading to the “Criticize Lin, Criticize Chen” campaign, referred to as the “Lin-Chen Anti-Party Clique.” Zhou Enlai’s early criticisms of Lin Biao also focused on “productivity theory” and Chen Boda’s reports from the Ninth National Congress [139][140]. In mid-September 1971, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China notified senior cadres about Lin Biao’s situation, which was communicated step by step after October, and in mid-December, three batches of materials were distributed, including “Crushing the Lin-Chen Anti-Party Clique’s Counter-Revolutionary Armed Coup” Part One, Two, and Three.

In September 1973, in the political report of the 10th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, Premier Zhou Enlai enumerated Lin Biao’s crimes: “Regarding the political report drafted by Chairman Mao, Lin Biao secretly supported Chen Boda’s public opposition, and only reluctantly accepted the Central Committee’s political line after being thwarted, reading the Central Committee’s political report at the conference. However, … Lin Biao, disregarding Chairman Mao and the Central Committee’s education, resistance, and rescue, continued to engage in conspiracy and sabotage, developing his plans to the point of an attempted counter-revolutionary coup at the Ninth Plenary Session of the Second Central Committee in August 1970, planning a counter-revolutionary armed coup with the ‘571 Project’ in March 1971, and launching a counter-revolutionary armed coup on September 8, attempting to harm the great leader Chairman Mao and establish a new central leadership. After the conspiracy failed, he fled by plane on September 13, defecting to the Soviet Union and betraying the party and country, eventually dying in a crash in Mongolia’s Wendu’erhan” [141].

In 1974, under Mao Zedong’s suggestion, Jiang Qing and others initiated the “Criticize Lin, Criticize Confucius” political movement, criticizing Lin Biao alongside Confucius, accusing him of “imitating Confucius in self-restraint and revival of rites, and attempting to restore capitalism.” The campaign later evolved into a critique of great Confucians, ultimately targeting Zhou Gong.

Evaluation of Lin Biao After the Cultural Revolution

Soon after Deng Xiaoping came to power following the downfall of the Gang of Four, writer Shu Yun described that Hu Yaobang, Tao Zhu’s wife, and others had suggested to Deng that Lin Biao’s case be reassessed. However, Deng, considering the stability of the domestic political situation, ultimately refused and issued a strict order prohibiting the overturning of Lin Biao’s case, emphasizing the need to tie Lin Biao with Jiang Qing [57]. From November 20, 1980, to January 15, 1981, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China’s special court tried the “Lin Biao and Jiang Qing Counter-Revolutionary Group” case.

Notification from the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China on the Trial of Lin Biao and Jiang Qing Counter-Revolutionary Group Case:

…… This trial is only for the criminal offenses of Lin Biao and Jiang Qing’s counter-revolutionary group, and does not address errors in work, including errors in political lines. The trial of Lin Biao and Jiang Qing’s counter-revolutionary group is to resolve contradictions between enemies and us, while handling errors in political lines is to resolve internal party issues. These two aspects must be clearly and strictly distinguished. We must not involve the mistakes and negligence of our party and state leaders in the trial of Lin Biao and Jiang Qing’s counter-revolutionary group.

On June 27, 1981, the 11th Central Committee’s Sixth Plenary Session passed the “Resolution on Certain Historical Issues of the Party Since the Founding of the People’s Republic of China,” publicly denouncing the Cultural Revolution. While the document pointed out that Mao Zedong should bear primary responsibility for the “errors initiated” during the Cultural Revolution, it also described that “ambitious individuals like Lin Biao, Jiang Qing, and Kang Sheng took advantage of and exacerbated these errors. This led to the initiation of the ‘Cultural Revolution.’” The text placed Lin Biao’s name ahead of Mao Zedong’s wife Jiang Qing. By the end of December, Chen Yun, Hu Yaobang, and Huang Kecheng, at the fifth national “Two Cases” trial work symposium, pointed out: “The Cultural Revolution was an ‘internal rebellion’ that occurred under complex conditions of errors made by our party and the Central Committee. Lin Biao and the ‘Gang of Four’ are different; they had merits in history” [142].

After the 1990s

In the early reform and opening-up period and the 1990s, references to the ten marshals by the Communist Party of China often omitted Lin Biao. However, evaluations became more objective after 2000. On the eve of the 80th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Liberation Army in 2007, Lin Biao’s photo appeared in the China People’s Revolutionary Military Museum for the first time in 30 years, correctly ordered according to the ten marshals (Lin Biao placed third). That year, the museum launched the “National Defense and Military Construction Achievements Exhibition,” featuring a life-sized image of Lin Biao in military uniform. Official media reported this using terms like “seeking truth from facts,” “objective attitude,” and “respect for history,” and the museum director explicitly stated: “In the future, Lin Biao will no longer be vilified.” His former residence has also been opened as a tourist memorial site. After 2013, the new sixth exhibition hall at Huanggang Museum in Huanggang City, Hubei Province, began displaying a statue of Lin Biao, marking the first appearance of Lin Biao’s statue in an official museum [143]. In historical and film dramas in mainland China, such as the “Great Battle” trilogy, Lin Biao is also frequently portrayed positively.

Personal Life

Diet and Daily Life

According to Lin Biao’s secretary Tan Yunhe, Lin Biao led a simple life with no special demands. Lin Biao did not engage in entertainment or pay much attention to his clothing and food. His cook was from Eastern Hebei and was also a communist party member, politically reliable but technically incompetent, though Lin Biao never complained. Lin Biao’s biggest trouble was poor sleep and insomnia. He liked cured meat because he read that it could help with sleep, although it actually had no such effect. A characteristic of Lin Biao’s daily life was that, whenever possible, even during the day, he preferred to close the curtains and turn on the lights, feeling that it made things quieter and helped him concentrate. Lin Biao did not enjoy exercise,He did not dance or enjoy playing; his exercise consisted of occasional walks outside[144]. Another interest of Lin Biao was to ride around in a car, often adjusting the car’s settings while he sat quietly in the vehicle thinking about various issues[145].

According to Lin Biao’s hygienist Liu Wenru, Lin Biao never ate fruits or drank water; he only snacked on peanut candy. Lin Biao generally had poor health, but he became excited and felt better whenever preparing for war. Additionally, Lin Biao could play the piano smoothly and enjoyed listening to light music and Mei Lanfang’s music[146].

Reading Life

According to Lin Biao’s secretary Tan Yunhe, Lin Biao’s mind was constantly busy with thoughts. Whenever he had to send a telegram during battles, he would lie down and dictate it without getting up to look at the map, which he memorized. He was very familiar with the enemy and friendly forces’ positions, the situation, and the terrain, all of which he diligently kept in mind. During marches and battles, his small briefcase, which had no lock, contained only single-volume editions of Chairman Mao’s works, such as “On Contradiction,” “On Practice,” strategic issues of the Anti-Japanese War, and guerrilla warfare strategies, along with a red and blue pencil. The books were filled with many marks, circles, and annotations, including marginal and confidential comments[147].

Honors

Chinese Soviet Republic First-Class Red Star Medal (Awarded on August 1, 1933, in Ruijin)

People’s Republic of China First-Class August 1st Medal (Awarded on September 27, 1955, in Beijing; revoked in 1980) First-Class Independence and Freedom Medal (Awarded on September 27, 1955, in Beijing; revoked in 1980) First-Class Liberation Medal (Awarded on September 27, 1955, in Beijing; revoked in 1980)

Works

Representative Works

- “On Brief Assaults,” published on June 17, 1934, in the fourth issue of “Revolutionary War”

- “Experiences from the Battle of Pingxingguan,” November 1937

- “Tactics of One Point and Two Sides,” December 1947 or early 1948

- “Long Live the Victory of People’s War——Commemorating the 20th Anniversary of the Victory of the Chinese People’s Anti-Japanese War,” August 1965

Collected Works

- “Selected Military Writings of Lin Biao,” edited by Lin Doudou and Liu Shufa, Hong Kong Cultural Revolution History Publishing House, 2012.

- “Collected Works of Lin Biao,” Hong Kong Zhonggang Media Publishing House, 2011.

- “Collected Works of Marshal Lin Biao” (Two Volumes), edited by Li De and Shu Yun, Phoenix Publishing, 2014. Claimed to be the most complete collection of Lin Biao’s works to date.

- Cultural Revolution Series Volumes 15-16, “Being a Good Student of Chairman Mao——Lin Biao and the Cultural Revolution” (Two Volumes), containing 94 documents by Lin Biao from May 1964 to October 1970, Taiwan Sisyphus Cultural Publishing Company, June 2016.

Others

- “Quotations of Vice Chairman Lin,” Wuhan, 1968. Modeled after “Quotations from Chairman Mao,” with thirty-one classified titles, 366 pages.

Family

Father: Lin Mingqing.

Lin Biao had six siblings, including the eldest sister and the youngest sister. The four brothers in between, from oldest to youngest, were named Qingfu, Yurong (Lin Biao), Yujin (Lin Cheng), and Xiangrong. The characters of the names for these four brothers were arranged according to the words “Zheng,” “Da,” “Guang,” and “Ming,” with Lin Biao’s character being “Zuoda” and his fourth brother Lin Xiangrong’s character being “Zuoming.” Lin Biao and Lin Xiangrong resembled their mother in appearance. Lin Xiangrong was less famous than his two cousins [Lin Yuying] and [Lin Yunan], who were martyrs. Lin Xiangrong died on the battlefield as the commander of the 590th Regiment, 197th Division, 66th Army, 20th Corps of the People’s Liberation Army during the Second Chinese Civil War [Battle of Taiyuan].

His child bride, Wang Jingyi, three years older than Lin Biao, saw Lin Biao flee from the marriage on their wedding night.

Ex-wife [Zhang Mei], a beauty from northern Shaanxi, married in 1937, and in 1941 gave birth to a daughter [Lin Xiaolin] in the Soviet Union.

Later wife [Ye Qun], married in Yan’an in 1943, gave birth to a daughter [Lin Liheng] (Doudou) in 1944 and a son [Lin Liguo] (Tigert) in 1945.

References

Citations

Yan Ming. “On the Scene of Lin Biao’s Plane Crash.” Book Excerpt. [2023-04-01]. (Original content archived on 2023-04-01).

Yan Ming. “On the Scene of Lin Biao’s Plane Crash.” Book Excerpt. [2023-04-01]. (Original content archived on 2023-04-01).

Lin Biao, Military Strategist, “Encyclopedia of China - Military Volume.”

“The First Set of Founding Fathers Pure Gold and Silver Commemorative Collection” Grand Release (Page archived, stored in the Internet Archive). The full set includes 83 pieces featuring Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, Liu Shaoqi, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun, Ren Bishi, and ten marshals, ten generals, and fifty-seven senior generals, with only a partial display shown; the full set is even more impressive.

“Revealed: Lin Biao and His Wife’s Final Moments at Building 96 in Beidaihe.” People’s Daily Online. 2011-04-22 [2018-08-07]. (Original content archived on 2020-04-30).

Yan Ming. “On the Scene of Lin Biao’s Plane Crash.” Book Excerpt. [2023-04-01]. (Original content archived on 2023-04-01).

“Outstanding Military Strategist and Founding Contributor; Marshal Lin Biao.” China News Network - Military. 2005-06-23 [2009-11-05]. (Original content archived on 2010-02-03).

“What Was the Total Number of Enemies Defeated by Our Army During the Liberation War?” “Xiangchao.” China Communist Party News Network. 2006 [2014-05-20]. (Original content archived on 2014-05-24). —— Regarding the exact total number of Nationalist Army casualties during the Liberation War, there have been varying figures and opinions due to different statistical perspectives and sources over time.

“The Life of Lin Biao,” Section 2, “Lin Biao Up to Age Thirteen.”

Jump to: 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 Lin Biao Overview, China Communist Party News Network, Retrieval Date November 2, 2009 [1] (Page archived, stored in the Internet Archive).

Jump to: 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 “Lin Biao’s Diary,” Chapter One, “1907-1925” [2] (Page archived, stored in the Internet Archive).

“The Lin Brothers: Lin Yuying, Lin Yunan, Lin Biao,” Section 67, “Cousin Helps Enter Secondary School.”

Jump to: 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 “The Lin Brothers: Lin Yuying, Lin Yunan, Lin Biao,” Section 68, “Applied for Military School and Changed Name.”

“The Super Trial: General Tumen Participates in the Trial of Lin Biao’s Counter-Revolutionary Group,” Xiao Sike, Jinan Publishing House, November 1992, ISBN 978-7-80572-669-4, Chapter Four, “The Leader Surrounded by Assassins.”

“The Lin Brothers: Lin Yuying, Lin Yunan, Lin Biao,” Section 71, “Battle of Huichang Against Qian Dajun.”

Jump to: 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 “Following Mao Zedong All My Life: Recollections of My Father, Founding General Chen Shiju,” Chen Renkang oral account, Jin Shan, Chen Yifeng, People’s Publishing House, 2007, ISBN 978-7-01-006105-4, Chapter “Lin Biao in My Father’s Eyes” [3] (Page archived, stored in the Internet Archive).

Jump to: 17.0 17.1 “The War Memoirs of Su Yu,” Su Yu, Intellectual Property Publishing House, 2005, ISBN 978-7-80198-209-4, Chapter Three, “Real Heroes,” Chapter Four, “During Strategic Transfers” [4] (Page archived, stored in the Internet Archive).

Jump to: 18.0 18.1 “Comrade Chen Yi’s Letter to Chairman Mao and Exposé of Lin Biao’s Anti-Party Crimes in His Early Years” Chen Yi, October 10, 1971, May-June 1972 Central Committee Report on Criticizing Lin and Rectification Meeting “Reference Documents” archived copy. [2009-11-09]. (Original content archived on October 16, 2008).

How Lin Biao, Who Almost Became a Defector, Became the Fourth Figure in Jinggangshan? (Page archived backup, stored in the Internet Archive) - History - Phoenix Net

Jump to: 20.0 20.1 “Comrade Xiao Ke’s Exposé on Lin Biao” Xiao Ke, November 20, 1971, May-June 1972 Central Committee Report on Criticizing Lin and Rectification Meeting “Reference Documents” archived copy. [2009-11-09]. (Original content archived on October 16, 2008).

“The Nanchang Uprising” edited by Xiao Ke, People’s Publishing House, July 1979.

“History of the Xiangnan Uprising” Li Liqing et al., compiled by the CCP Chenzhou Party History Data Collection Office, Hunan People’s Publishing House, November 1986.

“Leiyang Historical and Cultural Materials” compiled by the Literature and History Research Committee of the CPPCC Leiyang County Committee, 1985.

“The Uprising at the End of the Year in Leiyang,” “The Flames of War” Volume 1, People’s Literature Publishing House, 1964.

Jump to: 25.0 25.1 25.2 “Snow White and Blood Red” Chapter 9 “The Final Battle.”

“The Lin Brothers: Lin Yuying, Lin Yunan, Lin Biao” Section 75 “After Winning the Battle, Becoming Arrogant.”

“How Lin Biao, Who Almost Became a Defector, Became the Fourth Figure in Jinggangshan?” Miao Tijun, Dou Chunfang, “Party History Literature” Issue 7, 2008, ISSN 1007-6646 (Page archived backup, stored in the Internet Archive).

Jump to: 28.0 28.1 “Lin Biao’s Diary” Chapter 2 “1926-1933.”

“The Lin Brothers: Lin Yuying, Lin Yunan, Lin Biao” Section 73 “Leiyang Fights Two Battles in a Row.”

“The Lin Brothers: Lin Yuying, Lin Yunan, Lin Biao” Section 79 “Two Battles with Chen Guohui in Longyan.”

“History of the Communist Party of China” Central Literature Publishing House, Volume 1, Pages 269-270.

“The Lin Brothers: Lin Yuying, Lin Yunan, Lin Biao” Section 80 “Capturing Zhang Huizan Alive in Longgang.”

“The Soul of the Red Army: Famous Generals in the Long March” Zhu Shaojun, Wang Xiaoyang, CCP Party History Publishing House, 2006, ISBN 978-7-80199-374-8. “Pioneers of the Long March: Nie Rongzhen and Lin Biao’s Partnership” (Page archived backup, stored in the Internet Archive).

“Comrade Nie Rongzhen’s Letter to Chairman Mao and the Central Committee and Exposé of Lin Biao’s Anti-Party Crimes” Nie Rongzhen, November 28, 1971, May-June 1972 Central Committee Report on Criticizing Lin and Rectification Meeting “Reference Documents” archived copy. [2009-11-09]. (Original content archived on October 12, 2009).

“Memoirs of Nie Rongzhen” Nie Rongzhen, PLA Publishing House, August 2007, ISBN 978-7-5065-5423-7. “The Storm After the Zunyi Conference,” Chapter 25 “Several Issues Regarding Lin Biao,” etc.

“Comrade Li Fuchun Exposes Lin Biao’s Crimes” Li Fuchun, October 8, 1971, May-June 1972 Central Committee Report on Criticizing Lin and Rectification Meeting “Reference Documents” archived copy. [2009-11-09]. (Original content archived on October 16, 2008).

“The Lin Brothers: Lin Yuying, Lin Yunan, Lin Biao” Section 86 “Demanding the Replacement of Mao Zedong.”

“The Lin Brothers: Lin Yuying, Lin Yunan, Lin Biao” Section 87 “Leading Troops to Seize Luding Bridge.”

“Remembering the Long March” Yang Chengwu, Modern Education Publishing House, 2005, ISBN 978-7-80196-135-8, Chapter 13 “Seizing Luding Bridge.”

“Journey to the West” Edgar Snow, PLA Literature and Art Publishing House, 2002, ISBN 978-7-5033-1547-3, Fifth Part “The Hero of the Dadu River.”

“From Zunyi to Shaanbei” Liu Zhong, “The Red Flag Flies High” June 1960 (Page archived backup, stored in the Internet Archive).

“Breaking Through the ‘Heavenly Danger Line’” Zeng Guohua, “The Flames of War” Volume 4, PLA 30th Anniversary Essay Editing Committee, 1961.

Found telegrams dated September 14, 17, 21 (Mao Zedong’s instructions to Lin Biao before the “Pingxingguan Victory” in “Readings from Reports” August Issue), and 25.

“Hu and Wen Implicitly Clear Lin Biao’s Name” Chen Pokong, Hong Kong Open Magazine, September 2007 archived copy. [2009-11-09]. (Original content archived on February 15, 2010).

“Lin Biao Portrait” Chapter “Lin Biao’s Mother Died on the Escape Route in Liuzhou, Guangxi.”

“Liberation” Weekly, October 17. “An Outstanding Example of Upholding Mao Zedong Thought - The Collected Works of Vice Chairman Lin” compiled by the Proletarian Revolutionary Faction of the Air Force of the People’s Liberation Army, August 1968.

“Development History of the Eighth Route Army” Liu Maokun, Shanxi People’s Publishing House, 2005, ISBN 978-7-203-05372-9, Page 475 (Page archived backup, stored in the Internet Archive).

(Page archived backup, stored in the Internet Archive).

“How Broad Was Lin Biao’s Vision?” Huang Yao, “Party History Review” August 2009, ISSN 1005-1686 (Page archived backup, stored in the Internet Archive).

Wei Bihai: “The 115th Division’s Health Minister Talks About Lin Biao’s Injury,” “People’s Political Consultative Conference Newspaper - Spring and Autumn Weekly” April 13, 2001.

“Lin Biao’s Gunshot Injury Experience” Reporter interviewed the then 115th Division Health Minister Gu Guangshan on November 2, 2000, “People’s Political Consultative Conference Newspaper - Spring and Autumn Weekly” archived copy. [2009-11-12]. (Original content archived on July 18, 2011). (Page archived backup, stored in the Internet Archive)

“The Lin Brothers: Lin Yuying, Lin Yunan, Lin Biao” Section 92 “The Principal and Political Commissar in One.”

Jump to: 53.0 53.1 53.2 “Snow White and Blood Red” Chapter 12 “After Another ‘Retreat,’ Peace.”

Jump to: 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 54.4 54.5 “Lin Biao’s Bodyguard Li Wenpu Had to Say” Li Wenpu interviewed in December 1998, “Chinese Children” February 1999, ISSN 1003-0557.

“Reference Materials on the History of the CCP” edited by the Party History Teaching and Research Office of the Central Party School, People’s Publishing House, November 1979, Volume 4 “Anti-Japanese War Period” includes “On Short-Term Assaults.”

Luo Ruiqing’s 1972 Exposé of Lin Biao’s Materials (Page archived backup, stored in the Internet Archive)

Jump to: 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 57.4 “The Centenary of Lin Biao” Chapter “Defense of Marshal Lin Biao” (Page archived backup, stored in the Internet Archive).

“The Lin Brothers: Lin Yuying, Lin Yunan, Lin Biao” Section 96 “Debating Chiang Kai-shek in Chongqing.”

Jump to: 59.0 59.1 59.2 “Mao Zedong’s Selection of Lin Biao for the Northeast Strategy,” Yao Youzhi, Li Qingshan: “Record of the Liaoshen Campaign,” Baishan Publishing House, September 2008, ISBN: 9787806874684 Internet Archive’s backup, archived on April 2, 2015.

September 19, 1945, “Central Instructions on Strategic Policy of Northward Expansion and Southward Defense Given to Various Central Bureaus,” see “Selected Works of Liu Shaoqi,” Volume 1, Article 32. The specific content is: “(d) Establish the [[Central Bureau of Jireliao]], and expand the Jireliao Military Region, with Li Fuchun as the Secretary and Lin Biao as the Commander. Luo Ronghuan will work in the Northeast. Change the Shandong Bureau to the East China Bureau, with Chen Yi and Rao Shushi working in Shandong. The current Central China Bureau will be changed to a branch, under the command of the East China Bureau, with staff assigned separately.” [October 26, 2019]. (Original content archived on March 24, 2020).

Jump to: 61.0 61.1 61.2 61.3 61.4 Yan Jun: “Lin Biao’s Military Career,” 1945. [October 26, 2019]. (Original content archived on March 8, 2015).

“From Advancing into the Northeast to Nationwide Liberation,” “Liaoshen Campaign” Editorial Office, 1984; “The Magnificent Seventy Years of the Communist Party of China,” Central Party School Party History Teaching and Research Department, China Youth Publishing House, 1991, p. 226.

“Chronology of the Northeast Liberation War,” Ding Xiaochun, Ge Fulu, Wang Shiying eds., CCP Party History Data Publishing House, July 1987, ISBN 978-7-80023-007-3, p. 15.

“Military Data of the Three Years Northeast Liberation War,” Northeast Military Region Command of the People’s Liberation Army, October 1949, 196 pages.

“Snow White and Blood Red,” Chapter 8 “Dominating the Northeast.”

Jump to: 66.0 66.1 “Snow White and Blood Red,” Chapter 10 “The Unsettled Siping.”

“Snow White and Blood Red,” Chapter 11 “Spring in Winter.”

“Snow White and Blood Red,” Chapter 13 “Charm and Great Power,” Chapter 22 “Liberation.”

“Snow White and Blood Red,” Chapter 17 “Hot Snow.”

“Snow White and Blood Red,” Chapter 19 “Blood City.”

Jump to: 71.0 71.1 71.2 “Starting with Lin Biao Eating Soybeans,” Sun Zhiqiang, Sanlüe Observation Network [16] (Page archived, stored in the Internet Archive).

“Snow White and Blood Red,” Chapter 20 “Golden Autumn.”

Jump to: 73.0 73.1 73.2 “Lin Biao’s Diary,” Chapter 7 “1948-1949.”

“Snow White and Blood Red,” Chapter 30 “Neither Life Nor Death,” Chapter 31 “No Bloodshed.”

“Snow White and Blood Red,” Chapter 33 “Those Huts in Western Liaoning.”

“Snow White and Blood Red,” Chapter 18 “The Fox of the Black Land.”

Zhang Zhenglong: “Lin Biao Today is Just an Ordinary White-Collar Worker, Not a Big Official,” Zheng Liangen, “Jinan Times” [17] (Page archived, stored in the Internet Archive).

“Selected Military Papers of Marshal Lin Biao,” compiled by the Military Training Department, General Staff Headquarters, People’s Liberation Army (internal distribution), April 1961, pp. 118, 119, 128, 167, 168, 201-204, etc.

“Resolutely Implement the Work Guidelines of the Central China Bureau, Hubei Provincial Party Committee Sets Work Steps,” “Yangtze River Daily,” July 4, 1949 (or 14), B1 edition.

“Du Runsheng’s Autobiography: Major Decisions in Rural System Reform,” Du Runsheng, People’s Publishing House, 2005, ISBN 978-7-01-004979-3, pp. 2-3.

“The Dragon in Distress and Micro-Journey,” Quan Yanchi, China Federation of Literary and Art Circles Publishing House, May 2000, ISBN 978-7-5059-3606-5, Chapter “Yang Chengwu in 1967,” section “Meeting.”

Jump to: 82.0 82.1 “Mao Zedong’s Difficult Decisions—The Decision-Making Process of Chinese People’s Volunteer Army’s Deployment to Korea,” Wang Bo, China Social Sciences Press, October 2002, ISBN 978-7-5004-3557-0, pp. 143, 144, 162, 169.

“I Treated Lin Biao’s ‘Strange Illness’—Interview with Retired Veteran Chu Chengrui,” Jiang Xia, “Southern Weekend,” November 23, 2000 [18] (Page archived, stored in the Internet Archive) [19] (Page archived, stored in the Internet Archive).

Sohu History: Lin Biao Reveals the Astonishing Truths of the Korean War

“Lin Biao’s Diary,” Chapter 8 “1950-1958.” “Chronology of Nie Rongzhen,” Zhou Junlun, People’s Publishing House, 1999, ISBN 978-7-01-003046-3, Volume 2, p. 682.

Jump to: 86.0 86.1 “Review of Major Decisions and Events,” Bo Yibo, CCP Party History Publishing House, 2008, ISBN 978-7-80199-892-7, Chapter 30 “The ‘Anti-Rightist’ at the Lushan Conference” [20] (Page archived, stored in the Internet Archive).

Jump to: 87.0 87.1 “Man-Made Disasters,” Ding Shu, 90s Magazine Publishing House, 1991, ISBN 978-962-339-069-9, Chapter 8 “Anti-Rightist Famine Spread,” archived copy. [November 18, 2009]. (Original content archived on November 26, 2009). Archived copy. [November 18, 2009]. (Original content archived on October 15, 2009).

Lin Biao’s Candid Statement Clearing Peng Dehuai’s “Anti-Mao” False Accusation. [April 9, 2012]. (Original content archived on May 26, 2020).

One of Lin Biao’s “Five Tiger Generals,” Li Zuopeng, Passed Away, Previously Sentenced to 17 Years. [May 12, 2010]. (Original content archived on October 15, 2020).

Lin Biao’s General Qiu Huizuo’s Ups and Downs. [May 12, 2010]. (Original content archived on December 15, 2020).

The Political Career of Lin Biao’s Five Fierce Generals. [May 12, 2010]. (Original content archived on May 25, 2010).

Lin Biao Group’s Five Generals’ Ups and Downs: Huang Yongsheng. [May 12, 2010]. (Original content archived on December 15, 2020).

The Main Figure of Lin Biao’s Group Huang Yongsheng’s Scandals with Women. Internet Archive’s copy, archived on May 25, 2010.

Zhang Xueliang’s Fourth Brother Zhang Xuesi: Naval Talent Persecuted to Death During the Cultural Revolution. [May 12, 2010]. (Original content archived on July 20, 2020).

“Lin Biao’s Diary,” Chapter 9 “1959-1965.”

“The Giant Changes of Nuclear Industry in 50 Years: China’s Mushroom Cloud,” Meng Zhaorui, Liaoning People’s Publishing House, 2008, ISBN 978-7-205-06433-4, Section 26.

Jump to: 97.0 97.1 97.2 “Transformations—The Complete Story of the 7,000-Person Conference,” Zhang Suhua, China Youth Publishing House, June 2006, ISBN 978-7-5006-6792-6, Chapter “Lin Biao’s Temporary Decision to Abandon the Prepared Speech,” with remarks by Hu Sheng, who participated in drafting Liu Shaoqi’s written report [21] Archive.is copy, archived on August 21, 2006.

“‘Seven Thousand People Conference’ Lin Biao’s Speech Reanalysis” (Date: [April 15, 2008] Edition: [RB15] Page Title: [History] Source: [Southern Metropolis Daily] Author: ◎ Luo Tao)

“Mao Zedong Biography (1949-1976)” p. 1399.

“Lin Biao Illustrated Biography” Chapter “Lin Biao and Mao Zedong, Who Can Overthrow Luo Ruiqing.”

Guo Dajun. “Contemporary Chinese History.” Beijing Normal University Press. 2011: p. 158.

“What I Know About Ye Qun,” Guan Weixun, China Literature Publishing House, May 1993, ISBN 978-7-5071-0163-8, p. 215.

March 12, 2006, Shu Yun interviewed Ye Qun’s younger brother Ye Zhen’s notes, “A Century of Lin Biao” - “Defending Marshal Lin Biao.”

“Wang Guangmei Interviews,” Huang Zheng, Central Literature Publishing House, January 2006, pp. 10, 202, 406.

“Cultural Revolution Research Materials,” Volume 1, p. 85; “Chronology of the People’s Republic of China (1949-1992)” by Lin, Zheng Xinli, and Wang Ruipu, Red Flag Publishing House, 1993, ISBN 978-7-80068-577-4, Volume 3, p. 205.

“During the Cultural Revolution, I Was Lin Biao’s Secretary,” p. 239.

“During the Cultural Revolution, I Was Lin Biao’s Secretary,” Volume 1, p. 445.

“Cultural Revolution Research Materials,” Volume 1, p. 317.

“Maojiawan Documentary: Lin Biao’s Secretary Memoirs,” Chapter Eight, “The ‘Outstanding Chairman’ Fabrication.”

“Years of Great Turmoil: A Ten-Year History of the Cultural Revolution,” Wang Nianyi, Henan People’s Publishing House, September 2005, p. 373.

“Lin Biao’s Refusal to Wish Him ‘Everlasting Health,’” Yan Changgui, “Party History Review,” October 2004.

“During the Cultural Revolution, I Was Lin Biao’s Secretary,” pp. 95-96.

“Lin Biao’s Illustrated Biography,” “Preface.”

“Cultural Revolution Research Materials,” p. 87.

Archived Copy. [June 19, 2021]. (Original content archived on July 8, 2021).

“Zhou Enlai in His Later Years,” Gao Wenqian, Mirror Books Publishing House, April 2003, ISBN 978-1-932138-07-8, Archived Copy. [November 9, 2009]. (Original content archived on May 29, 2010).

“Maojiawan Documentary: Lin Biao’s Secretary Memoirs,” p. 329.

Skip to: 118.0 118.1 Wang Nianyi, He Shu’s “Analysis of the ‘Chairman of the State’ Issue,” “Huaxia Digest Supplement Issue 224 - Cultural Revolution Museum Newsletter Issue 70,” published July 13, 2000.

Jin Chongji, ed., “Biography of Zhou Enlai - Volume Two,” Beijing, Central Literature Publishing House, 1998, p. 1970.

Qiu Huizuo, “Memoirs of Qiu Huizuo,” New Century Publishing House, January 2011.

Wang Nianyi, He Shu: “Re-discussion of the 1970 Lushan Conference and the Origins of the Mao Zedong-Lin Biao Conflict - Behind the ‘Chairman of the State’ Dispute,” originally published in the American “Contemporary China Studies,” Issue 1, 2001.

“Years of Hardship,” Wu Faxian Memoirs, Hong Kong: Hong Kong Beixing Publishing House, 2006.

“Chen Boda’s Final Oral Memoirs,” compiled by Chen Xiaonong (son of Chen Boda), Sunshine Global Publishing Hong Kong Limited, March 2005, ISBN 978-988-98295-1-3, Chapter “Years of the Cultural Revolution,” “Mystery of the Ninth Central Committee’s Second Plenary Session.”

“Years of Hardship,” Wu Faxian Memoirs, Hong Kong: Beixing Publishing House, September 2006.

“Conversations Between Chairman Mao and Responsible Comrades Along the Route During His Tour,” Central Committee Document 12, December 1972.

“Years of Hardship,” Wu Faxian Memoirs, Hong Kong: Beixing Publishing House, September 2006.

“March 22, 1971: Lin Biao Ordered Lin Liguo and Others to Draft the ‘571 Project Summary’,” China Communist Party News [22] (Page archived, stored in Internet Archive).

“Mao Zedong’s Key Decisions Before the Lin Biao Incident,” Cao Ying, China Communist Party News [23] (Page archived, stored in Internet Archive).

Li Zuopeng Talks About “September 13”: It Would Have Been Easy for the Premier to Stop Lin Biao’s Plane – History and Culture – People’s Daily Online. [July 30, 2012]. (Original content archived on August 24, 2020).

“Biography of Mao Zedong (1949-1976),” Chapter “Lin Biao Incident.”

“Lin Biao’s Escape and Crash Death,” China Communist Party News, search date November 2, 2009 [24] (Page archived, stored in Internet Archive).

“What I Know About Ye Qun,” Guan Weixun, China Literature Publishing House, May 1993, p. 121.

“Biography of Mao Zedong (1949-1976),” Chapter “Domestic and Foreign Affairs in 1972.”

One is “Central Committee Document No. 1, January 1974,” “Lin Biao and Confucianism (Material One),” January 1974.

Turning Point Moments (1970-1979) (Detailed Explanation of Major Chinese Historical Events). Authors: Deng Shujie, Li Mei, Wu Xiaoli, Su Jihong. [October 31, 2020]. (Original content archived on December 15, 2020).

“A Brief History of the Cultural Revolution,” Xi Xuan, Jin Chunming, CCP History Publishing House, 2006, ISBN 978-7-80199-392-2, p. 391 [25] (Page archived, stored in Internet Archive).

China Review, Issues 456-481, p. 17, Taiwan China Review Society.

“Children of the Red Emperor”: Lin Biao Was the Designated Successor, So Why Did He Attempt to Harm Chairman Mao? [June 19, 2021]. (Original content archived on July 8, 2021).

October 24, 1971, “People’s Daily” published an article signed “Li Cheng”: “The Revolutionary Essence of the Lin Biao Clique’s Advocacy of the Productivity Theory,” Criticizing Lin Biao’s so-called “Productivity Theory” that the main task after the ‘Nine Major’ was to develop production.

“People’s Daily” April 4, 1975, published [Lin Biao Clique’s Call for ‘People’s Prosperity’ - What Is Their Intention?] Criticizing the Lin Biao clique’s advocacy for building a “truly socialist” “rich and strong country,” this reactionary slogan.

Revealed: Why the “Gang of Four” Was Initially Criticized as Extreme Rightists. Sina. [August 4, 2013]. (Original content archived on May 23, 2012).

Central Committee Document “Document No. 82-9, January 31, 1982,” “Super Trial,” p. 698.

Sixth Exhibition Hall, Exhibition Line 16. (Original content archived on March 18, 2015).

Lin Biao Through the Eyes of His Secretary: Simple Living, No Special Demands. Phoenix News. [September 8, 2011]. (Original content archived on June 4, 2020).

Lin Biao’s Internal Affairs Recalled by His Secretary (Chu Chengrui). [November 4, 2012]. (Original content archived on March 5, 2016).

Soldier’s First Encounter with Lin Biao Left Him Shocked: Why So Sickly? m.sohu.com. [March 5, 2023]. (Original content archived on March 5, 2023).

Lin Biao’s Secretary Recalled: Lin Biao Was Not Picky About Entertainment, and He Never Complained About Poor Cooking Skills. Phoenix News. [January 6, 2012]. (Original content archived on June 4, 2020).

Chiang Kai-shek Once Called Lin Biao “Contemporary Han Xin.” Phoenix News. [October 24, 2011]. (Original content archived on October 28, 2011).

Mao Zedong’s Evaluation of Lin Biao: Not Only Capable but Also a Genius of the Era. Wu Luxiang. Phoenix News. [September 1, 2011]. (Original content archived on June 4, 2020).

Su Yu on Criticizing Lin Biao: Lin Biao’s Death Brought Up All the Old Grievances. Zhang Xiongwen. Phoenix News. [December 18, 2011]. (Original content archived on June 4, 2020).

Lin Biao’s Plane Crash: Chen Yun’s Reflection: How Could This Person Be So Heartless. Global Times. [December 30, 2011]. (Original content archived on January 8, 2012).

Huang Kecheng on Lin Biao: Writing Him as Worthless Does Not Reflect the Facts. Phoenix News. [September 9, 2011]. (Original content archived on June 4, 2020).

Yang Shangkun: Writing about Lin Biao must be based on facts. Phoenix News. [September 11, 2011]. (Original content archived on June 4, 2020) (Chinese (Simplified)).

Secretary recalls Lin Biao: “Many evaluations of Comrade Lin are not true.” Phoenix News. [September 4, 2011]. (Original content archived on June 4, 2020) (Chinese (Simplified)).

People’s Daily criticizes Lin: Ambitious, schemer, two-faced, traitor. Phoenix News. [September 11, 2011]. (Original content archived on June 4, 2020) (Chinese (Simplified)).

Jiang Qing: Lin Biao is a great thief and embezzler. He should learn from Song Jiang to undermine Chao Gai. September 11, 2011. (Original content archived on June 4, 2020) (Chinese (Simplified)).

Source: Wikipedia

Related Content

- Mao Zedong and Lin Biao:The Mystery of the First Faction's Defection(Part 2)

- Lin Biao:The Rise and Fall of a Military Genius (Part 1)

- Deng Xiaoping:The Architect of Modern China (Part 2)

- Deng Xiaoping:The Architect of Modern China (Part 1)

- Moment of Revelation:Mao Zedong's Loyal Subject Zhou Enlai (Complete Version)